Prologue

Generated by ChatGPT

When Jeanie McLean stepped off the ship on a chilly London morning in the spring of 1938, it was the first time she had set foot in Britain in 17 years. The salty sea air was replaced by a swirl of sounds – shouting porters, clattering carts, and the steady hum of the bustling city. Though her voyage on the Rangitata, a large modern liner, had been relatively comfortable, after 33 long days at sea she was likely grateful for solid ground beneath her feet. She may also have felt a sense of nervous anticipation about what lay ahead. It wouldn’t be long before she was reunited with Mary, the daughter she had left behind in Scotland all those years ago.

Humble Beginnings

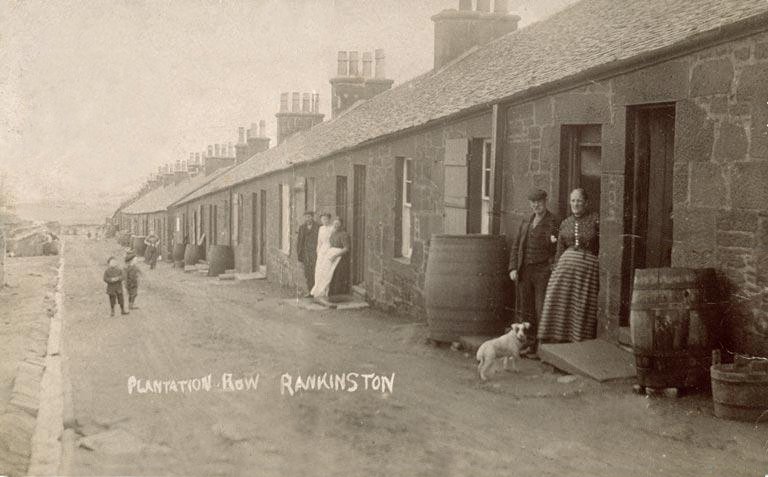

Jane “Jeanie” Shearer was born in Maryhill, Glasgow on 23 December 1870[1]. She was the second child of John Shearer, an ironstone miner, and his wife Mary Ann. Her grandparents had come over from Ireland with the “tatty howkers” in the 1830s – harvesting potatoes on the Ayrshire coast[2]. By the age of 10 her family had moved to the parish of Coylton near Ayr and she had 3 younger siblings: Mary, Jock and Rab[3]. Two other brothers had sadly died before she turned two[4]. They lived in a terraced row of miner’s cottages in the village of Rankinston, each very basic with just one room and a kitchen. An outside toilet was shared with 4 other houses[5]. The family were poor and clearly struggling as in 1879 Jeanie’s mother was charged with stealing money from a public house in Ayr and her father with “reset” (handling stolen goods). They both pleaded guilty and were sentenced to 40 days in prison[6]. Being the eldest child, and especially as a daughter, Jeanie would probably have been entrusted with caring for her younger siblings and maintaining order in her parents’ absence. This responsibility would likely have increased over the next few years, as the family struggled on in Coylton and more cracks began to show.

Their difficulties culminated in late 1884 when Jeanie’s father John left the family to find mining work in America with his brother, Thomas[7]. Mary Ann was pregnant with fifth child Charles at the time and may well have been forced to apply for poor relief with him gone. She soon got together with another miner, William Thom, with whom she had a child, Jeanie’s half-sister Janet, in 1886[8]. Although they were unable to marry with John still alive, it was common for widowed or abandoned women to find new partners quickly to support their family. A family rumour has it that John, meanwhile, who Mary never heard from again, was tempted by the Klondike Gold Rush and died in a bar room brawl in Yukon, Canada around 1900[9](although there is no direct evidence to support this)

With her father gone, and mother re-establishing herself in Coylton, Jeanie had to make her own way. She crossed the country to Fife where she stayed with her aunt Sarah and family in Crossgates, near Dunfermline, and took up work as a cloth finisher and beetler[10]. It was common for women to be employed in the linen industry, especially in the lighter but still skilled work of finishing. Jeanie was likely employed in one of Dunfermline’s many damask mills such as the St Leonard’s Works run by the world-renowned Erskine Beveridge & Co[11]. She would have worked long tiring hours lifting, folding and turning heavy cloth, surrounded by the constant pounding of heavy wooden hammers[12].

Marriage and Loss

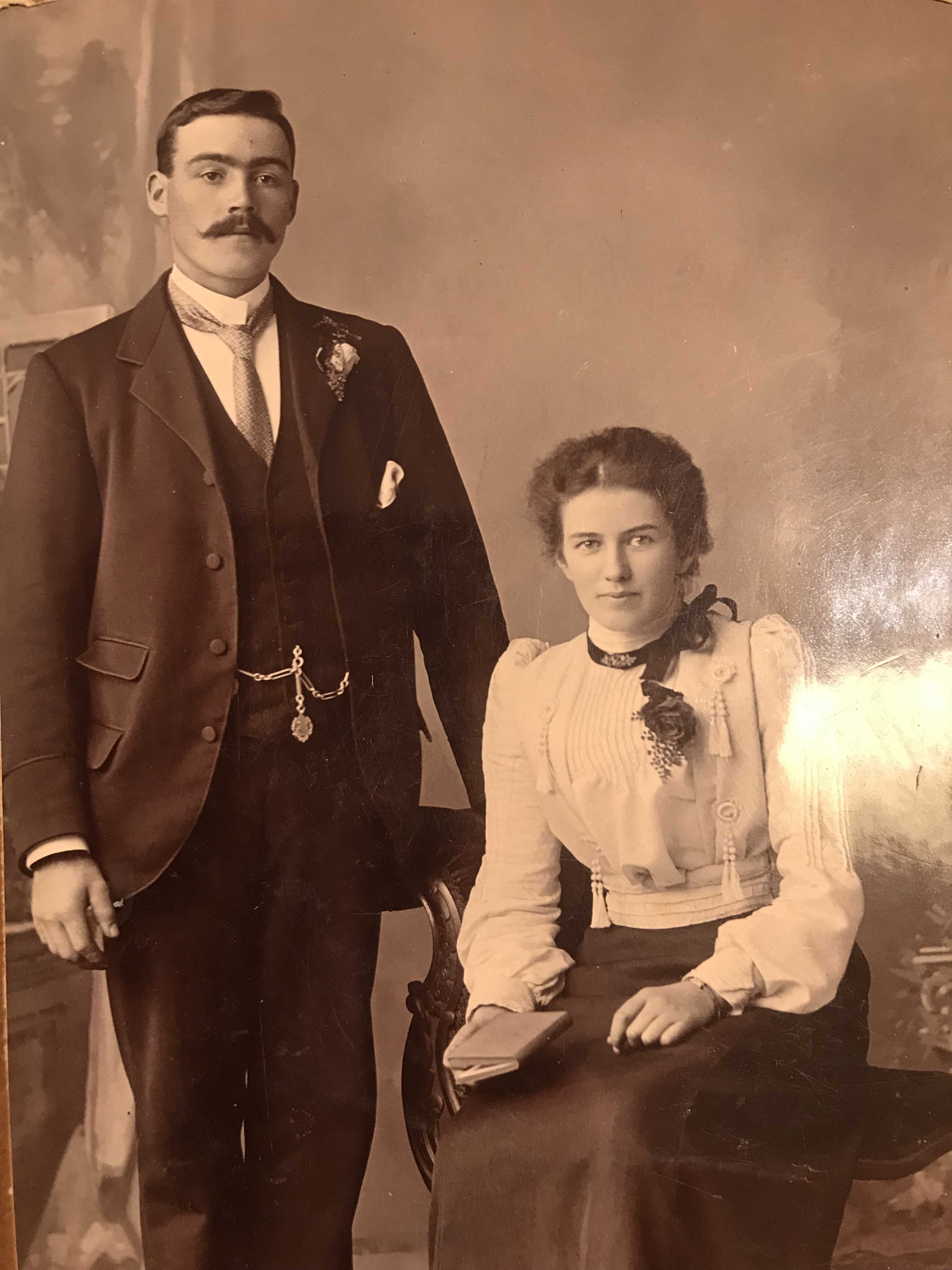

It was here, in her early twenties, that she met coal miner Archibald McLean, perhaps through his sister Minto who was a local linen weaver[13]. They married at the Viewfield Baptist Church in Dunfermline on 14th April 1893[14]. Over the next 15 years, Jeanie and Archibald had 10 children, 8 of whom survived into adulthood, including Mary (my great grandmother) born in 1897[15]. They lived in the little old village of Milesmark[16], a few miles west of Dunfermline where many of the men worked in local mines. When they first moved in together the area had poor sanitation and dangerously unmaintained roads[17], but over time the local mine owners John Nimmo & Sons carried out extensive improvements and modernisation[18]. Daughter Mary later recollected that Archibald’s father also lived with them for a short time during this period, although he and Jeanie didn’t get on and were always fighting – because she was so “domineering”, Mary said[19].

Archibald himself was a good man and a hard worker. With a £500 loan from the Dunfermline Building Society he built four houses (known as the McLean Buildings in Whitemyre[20]): one for his growing family and the others to rent out[21]. It was a step up that few miners made, and for the first time Jeanie must have felt settled and secure, looking after her home and children. Her husband, however, had health problems. Having already had a stroke which affected his left side, one Sunday afternoon in May 1909 he suffered a fatal brain haemorrhage[22]. 12-year-old Mary, coming home from Sunday School, was met by her friend running down and calling out “your father’s deed, your father’s deed!”[23]Jeanie was left with 9 children and the houses and finances to maintain, making a painful time even more stressful. To make things worse, her 2-year-old son James also died 18 months later from a respiratory infection[24]. Now reliant on her older children for financial support, sons Archibald (known as Baldy) and Jock took up dangerous work as ‘coal drawers’, hauling heavy carts up from the pit, while young Mary was exempted from school and followed in her mother’s footsteps as a power loom weaver in a linen factory[25]. Jeanie got a job starching collars and cuffs of shirts at a laundry[26]. Having been upwardly mobile while Archibald was alive, one can imagine Jeanie being scared of being plunged back into poverty and losing her hard-fought social status.

A divided family

In the years that followed Baldy, keen to provide for his family, followed his friend out to New Zealand where, with echoes of his grandfather John Shearer, he sought a wage in the gold mines of Otago[27]. This was mechanised underground mining by this point, not the romantic digger with pan and shovel, and Baldy earned enough to send money back home to his mother every month.

Second son Jock joined the army, enlisting with the Gordon Highlanders in 1914, and made the rank of Lance Corporal before being invalided in France[28]. He had reached the western front in May 1915 and been posted to the 2nd Battalion after they suffered heavy losses at Festubert. By July however he had been hospitalised with sciatica and returned to England in September. After recovering at Seafield War Hospital in Leith, he was discharged from duty in 1916 and got assistance to join brother Baldy in New Zealand.

Mary, meanwhile, who described herself as “always in trouble”, “a right devil”, and “a big tomboy that ran with all the lads” went into service at a manse in nearby Culross[29]. It was here, at the age of 20, that a coal miner named Willie Paterson became infatuated with her and pursued her relentlessly. Word had evidently got back to Jeanie about her daughter’s admirer and things came to a head on a sunny Friday in July 1917. According to Mary, she had taken leave from work to find Willie and urge him to back off when they were confronted in the street by Jeanie. She accused Mary of “disgracing the family” and marched them down to Dunfermline Town Hall to get married there and then. A warrant was obtained from a local judge to proceed without the usual notice period and Jeanie got a girl she knew called Millie Hamilton to act as witness alongside Willie’s friend[30]. We only have Mary’s version of this story but recounting it 60 years later she still sounded angry at her mother (who she described as a “prude”) and the sense of injustice was clear to hear.

New Zealand Bound

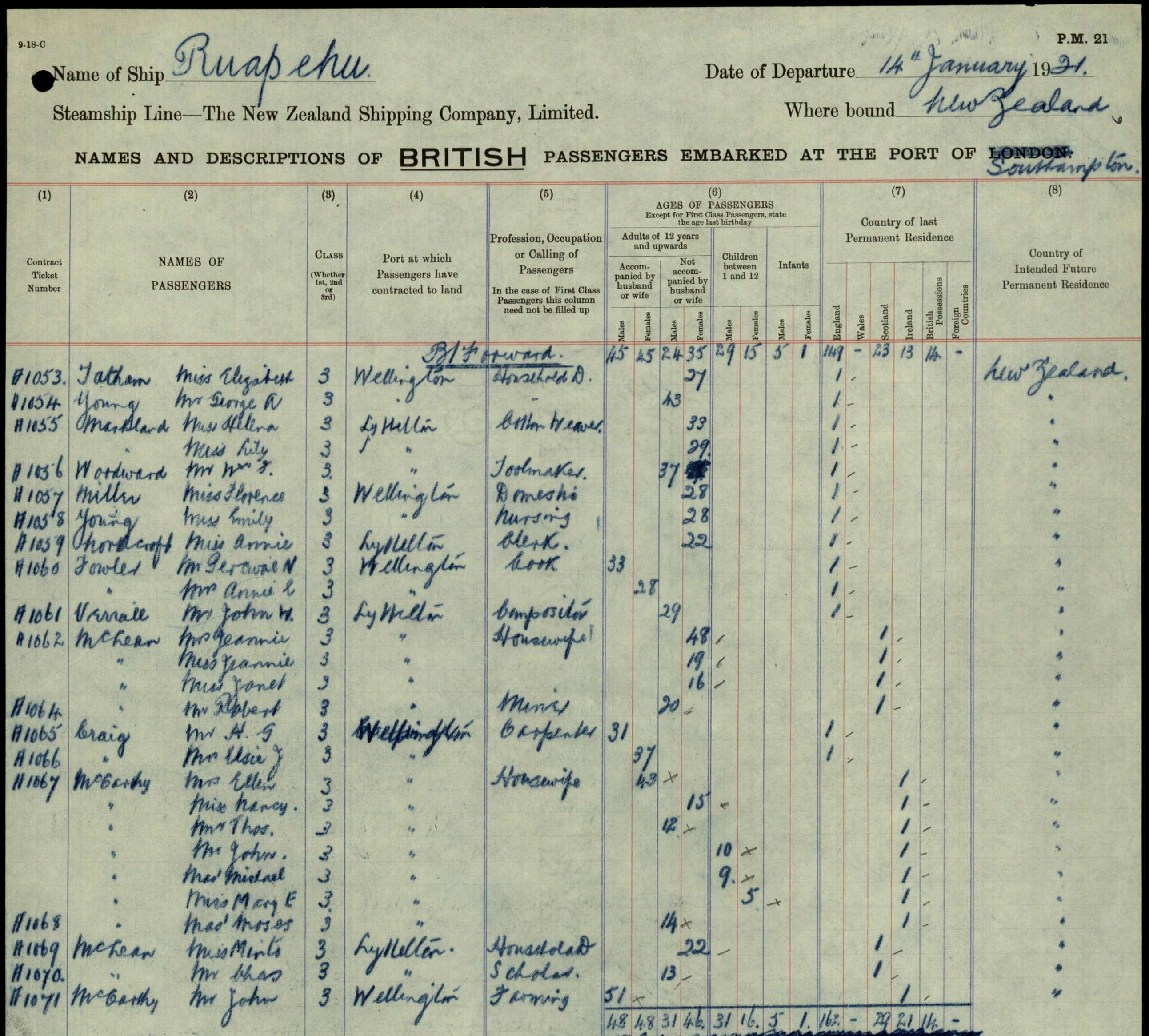

With Mary married off to Willie Paterson and Baldy and Jock settled in New Zealand, Jeanie was considering her options for a better life for herself and the remaining children. Her sister Mary and husband Thomas McCloy had also emigrated to New Zealand and were living near Dunedin on the south island[31]. The country found rising prosperity during and immediately after the Great War and assisted immigration from the UK increased sharply in 1919 and the early 1920s, particularly among Scots[32]. Post-war depression was acutely felt in Scotland and by 1921, with financial help from Baldy, Jeanie decided that the opportunity had come to make a drastic change. It was thus in January of that year at the age of 50, that she packed up all of her belongings into a big van, including her precious sewing machine, and made her way to the port at Southampton with Minty (22), Rab (20), Jean (19), Jenny (16) and Charlie (13), but not Mary. Baldy had apparently sent money for her to travel too, but their mother kept it[33].

Whether that was true or not, we know that Jeanie and her other 5 children boarded the steam ship RMS Ruapehu on 14 Jan 1921[34]and embarked on a 7-week voyage to their new home, leaving Mary behind in Dunfermline just 5 days before her first (live) baby was born[35]. Perhaps tellingly, Mary named her daughter Jeanie. Her mother entrusted her with looking after the houses when she was gone[36].

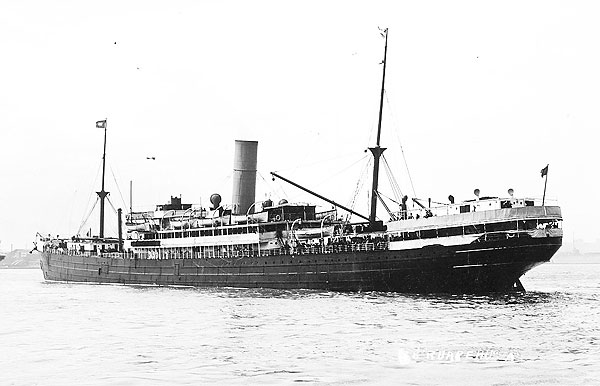

Although first launched in 1901, the Ruapehu had been completely refitted after serving in the First World War[37]. The family travelled in third class accommodation[38]which meant they had their own cabins but on the lower decks near to the noise and vibrations of the engines. Safety would still have been a concern with the Titanic disaster only 9 years previous, although improvements had been made since then. Luckily for the McLeans, a new route had also recently opened up via the Panama Canal which promised a faster and smoother journey[39].

After rough weather crossing the Atlantic, the Ruapehu found calmer waters and proceeded to Jamaica, along the Panama Canal and to Pitcairn Island in the southern Pacific. Although food was plentiful, passengers complained that it was very plain and badly cooked. The cabins were also so poorly ventilated that women and children had to sleep on deck[40].

From Pitcairn, the ship and its 268 passengers made slow progress towards New Zealand, arriving in Wellington 2 weeks later than scheduled on the 6th March and in Lyttelton on the South Island the next morning[41]. The McLeans disembarked on a warm, cloudy but dry day[42]and continued the last leg of their long journey to their final destination of Mosgiel near Dunedin. With the green pasture of the Taieri Plain opening up before them and the Maungatua Range rising steeply in the west, the high chimney stack of the Mosgiel woollen mill was a beacon, welcoming the family to their new life[43].

Life in New Zealand

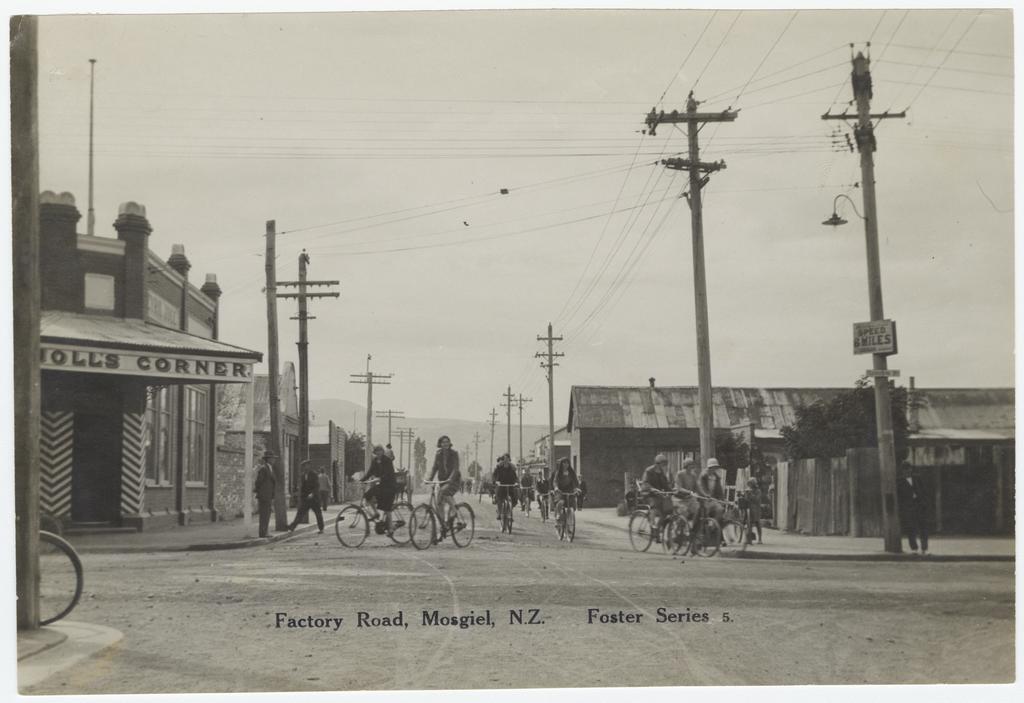

Jeanie and the children joined Baldy in Mosgiel, settling first on Factory Road, near the famous woollen mill[44]. In 1927 she bought property in nearby Wickliffe Street[45], while her sister Mary lived just around the corner on Argyle Street[46]. Mosgiel at that time was a close-knit, largely Scottish-settled town, its life revolving around the woollen mill, Presbyterian church, and regular community events in Mosgiel Park[47].

Jeanie’s life likely centred on the home, her extended family, and the church. She may have attended services and women’s groups at the Baptist Church, joined in the annual mill picnic, and listened to Mosgiel’s brass band playing in the park on summer afternoons. She may also have done part-time sewing or taken work at the woollen mill, as many local women did, alongside the constant demands of housework.

The economic hardship of the Great Depression in the late 1920s and early 1930s would have been felt in Mosgiel, with shortages and tightened budgets becoming part of everyday life. Through these years Jeanie remained a widow, her social respectability grounded in her faith, hard work, and strong family connections

As the years passed the children began to establish themselves: Baldy gave up mining to work as a taxi driver[48] Jock moved to Australia, married Jeannie and had a daughter Heather; Minty married Henry Philp, a hospital attendant, and had 3 children; Rab became a metal worker and married Agnes; Jenny married Frank Seller, a fitter, and had 2 children; Charlie worked as a pattern maker, married Grace and had children Lyall and Valda; and Jean stayed living with Jeanie and remained unmarried[49]

Back in Scotland, Mary’s first husband had died young from silicosis[50], a lung disease common amongst miners. She remarried David Cuthbertson and had four more children – two boys and two girls – including my grandmother Dina, born in 1927[51]. By 1938, David had started a new job in Nottingham and the family were preparing to leave Scotland. Jean, the baby born just days after Jeanie had sailed for New Zealand, was now 17. Neither she nor any of her younger siblings had ever met their grandmother. Meanwhile Jeanie, aged 67 by this time, was making plans of her own. Having left Mary behind all those years ago, she decided the time had come to make the long journey back to Scotland and finally meet the grandchildren she had only heard about.

The Reunion

The trip was a large undertaking. Given the length of the voyage, Jeanie planned to stay away for a year or more. In a sign of her preparedness she went to a solicitor in Mosgiel on 15 March to make a will. She bequeathed all her property to Jean, her only unmarried daughter[52].

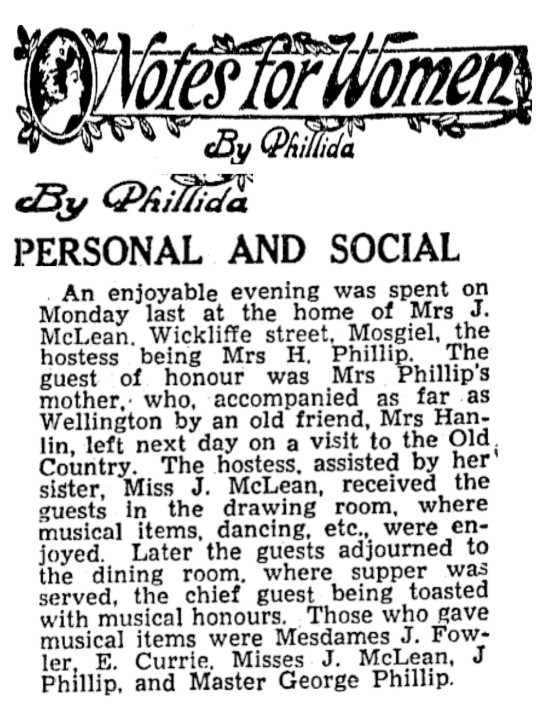

Then the evening before she was due to set off her daughter Minty put on a leaving party at Jeanie’s house on Wickcliffe Street. There was food, music and dancing with performances by her grandchildren in her honour[53].

The next day, 29 March, she departed for Wellington accompanied by her old friend Mrs Hanlin, and on 7 April 1938 set sail for “the Old Country” on board the Rangitata. The memories of her journey many years ago must have come flooding back, although this time she would be making the trip alone.

Once safely in England, Jeanie made her way up to Glasgow to the bungalow on a newly-built estate in Mount Vernon where Mary and her family lived. Mary’s daughter Dina recalled this visit and getting to know “Granny McLean” for the first time. She remembered her as an imposing figure, a “very tall big woman” who “stood very straight” and that her mother and grandmother were always falling out, perhaps suggesting that they fell back easily into old patterns of behaviour[54].

Despite their differences, Jeanie stayed with them on and off for over 6 months. During her time there they visited the new MacFarlane Lang biscuit factory in Glasgow but on their way home an unfortunate incident occurred. Jeanie, Mary and her youngest son David were hit by a taxi as they crossed the road. Six year old David was badly injured although did eventually recover from his fractured arms, legs and head wound after months of intensive care[55].

Jeanie and Mary escaped with minor injuries but their time together was nevertheless cut short due to talk of another impending war. Jeanie was forced to rush back to New Zealand earlier than planned and said goodbye to her eldest daughter for the second and last time.

Epilogue

On her return to Mosgiel, Jeanie remained at 7 Wickliffe Street with daughter Jean[56]. When war did break out New Zealand joined simultaneously with Britain on 3 Sep 1939. Although the New Zealanders were relatively lucky with no fighting or occupation on home soil, families were still disrupted and there was a constant threat and uncertainty for six years. Those, like Jeanie, who remembered the losses of the First World War would have been particularly fraught as their sons were called up. Both Charlie (35) and Rab (41) were enlisted in 1942 for overseas and home service respectively[57]. Jeanie’s resourcefulness would have come in handy as rationing of food and fabrics was imposed.

After the war was over, Jeanie lived out her days in Mosgiel and became a great grandmother several times over. Although she never saw daughter Mary again, Baldy did visit her in Nottingham years later[58]and no doubt brought back news of her latest great-grandchild, Dina’s son Alan.

As she got older Jeanie developed arteriosclerosis and died at home, aged 86, from bronchopneumonia on 7 June 1957[59]. Her cremation 3 days later, officiated by a Baptist minister, was held at Anderson’s Bay Cemetery[60]. Her sister Mary, who came to New Zealand before her, had died 5 years earlier[61].

When Dina and her husband Doug visited New Zealand in 1990 they went to see Jeanie’s only surviving child, Jean, in a nursing home and asked her why the family had left Mary behind in Scotland. Although her mind was failing, Jean replied: “Moll couldn’t come. Moll was a bad girl, she had a baby.[62]” It would seem that the family shame borne from Jeanie’s strong sense of moral respectability lived on long beyond her own passing, although it did not break the bonds of the McLeans or their descendants.

References

[1] Birth certificate of Jane Shearer

[2] Recording of Mary Maclean talking to Dina and Martin Maclean, c1978

[3] 1881 census for household of John Shearer in Coylton, Ayrshire

[4] Statutory Birth/Death register indexes, Scotland’s People

[5] Ayrshire Miners’ Rows: Section 3, ayrshirehistory.org.uk

[6] Ayr Advertiser, 14 Aug 1879

[7] Research by Ancestry user DavidGordon21, New York Passenger Lists (1820-1957), Mary Shearer Poor Relief Application 5 Oct 1885

[8] 1891 census for household of Mary Ann Shearer in Coylton, Ayrshire

[9] DavidGordon21 (via Elizabeth Riley née Shearer)

[10] 1891 census for household of Joseph McGill, Crossgates, Fife

[11] Erskine Beveridge & Co. The Origins of a Famous Dunfermline Business by Donald Adamson, https://dunfermlinehistsoc.org.uk/erskine-beveridges-business-beginnings/

[12] The Damask Trade in Dunfermline 1750-1885, Catherine Mary Margaret Chorley, 2023

[13] 1891 census for household of Archibald McLean, Dunfermline, Fife

[14] Marriage certificate of Archibald McLean and Jane Shearer

[15] 1901 census for household of Archibald McLean in Carnock, Fife; email from Lyall McLean (6 Oct 2010)

[16] Recording of Mary Maclean

[17] St Andrews Citizen, 11 Feb 1893

[18] Dunfermline Journal, 9 Feb 1895

[19] Recording of Mary Maclean

[20] 1921 census for household of William Paterson, Dunfermline, Fife

[21] Recording of Mary Maclean

[22] Death certificate of Archibald McLean

[23] Recording of Mary Maclean

[24] Transcription of death certificate of James McLean

[25] 1911 census for household of Jeanie McLean, Whitemyre, Dunfermline

[26] Recording of Mary Maclean

[27] Ibid.

[28] Service record of John McLean (4271)

[29] Recording of Mary Maclean

[30] Marriage certificate of William Paterson and Mary McLean

[31] New Zealand electoral rolls, 1914

[32] The interwar immigrants, 1916-1945. https://nzhistory.govt.nz/

[33] Recording of Mary Maclean

[34] UK, Outward Passenger Lists, 1890-1960

[35] Birth certificate of Jeanie Paterson

[36] Recording of Mary Maclean

[37] http://ssmaritime.com/Ruapehu.htm

[38] UK, Outward Passenger Lists, 1890-1960

[39] ssmaritime.com

[40] The Star (Christchurch), 7 Mar 1921

[41] Evening Post, 25 Feb 1921

[42] Otago Daily Times

[43] https://dunedin.recollect.co.nz/nodes/view/200981

[44] New Zealand electoral rolls, 1922

[45] Evening Star, 13 Sep 1927

[46] New Zealand electoral rolls, 1925

[47] ChatGPT, citing Taieri Buildings (1979, Knight & Wales), Mosgiel and its Mill (1976, Leach), Otago Daily Times etc.

[48] New Zealand electoral rolls, 1925

[49] Emails from Lyall McLean, Oct 2010; New Zealand electoral rolls

[50] Recording of Mary Maclean

[51] History and experiences of Davidina MacLean (2019)

[52] Will of Jeanie McLean

[53] Otago Daily Times, 9 Apr 1938

[54] Recording of interview with Dina Maclean, 3 June 2010

[55] History and experiences of Davidina MacLean

[56] New Zealand electoral rolls, 1943

[57] New Zealand, World War II Ballot Lists, 1942

[58] Recording of interview with Dina Maclean; UK Incoming Passenger Lists, 28 July 1951

[59] Death certificate of Jeanie McLean

[60] New Zealand, Cemetery Records, 1957

[61] New Zealand, Cemetery Records, 1952

[62] Recording of interview with Dina Maclean