Sam and Sarah Mattock were married for 42 years and became pillars of the community in the village of Helpringham in Lincolnshire. From inauspicious beginnings they forged their own path and dedicated themselves to helping both the young and old of their local area, despite lives punctuated with tragedy. Sam was a competent and energetic man, one of Helpringham’s first parish councillors1 and served as Superintendent of the Sunday School for over 20 years2. The two of them were heavily involved in the Primitive Methodist Chapel with Sam as a preacher, secretary and trustee, and Sarah a dedicated organiser and caterer of local events and member of the choir. They had four children together, living for many years in Rose Cottage near to the centre of the village, with Sam spending most of his days working on the railway.

A Young Bride and an Early Start

Sarah Ann Warrington was born in Heckington3, a large village on the road from Boston to Sleaford, nestled among lush pastures with views across the Fens. She was only 16 when she married 22-year-old farm labourer Sam Mattock in the spring of 1880, though she listed her age as 19 on the marriage register4. Already two months pregnant, she may have felt the urgency of marriage, perhaps encouraged by her widowed mother, Jane, who worked as a charwoman to make ends meet. Sarah’s father, Fred Warrington, had died when she was only 25.

Sam had moved north from his family home 20 miles away near Holbeach6. His father was a shepherd, while Sarah’s brothers were all farm labourers so they likely met through mutual acquaintances or at a local agricultural show or fair.

The wedding took place at the Register Office in Sleaford, a choice often made for reasons of privacy and affordability7—particularly for young couples in Sarah and Sam’s situation. The witnesses were their close friends, George and Sarah Houlden, siblings of a similar age8. Just six months later, on 30 November 1880, their first child, Clara Jane, was born, her middle name a tribute to her grandmother.

In the 1881 census9 Sam, Sarah, and baby Clara were recorded at Jane’s house in Heckington. Perhaps they were visiting, or maybe, like many young couples, they had no choice but to share a roof with family while saving for a home of their own. Over the next few years, their family grew with the arrival of Charles in 1883 and Annie in 188510. But joy turned to heartbreak when little Annie contracted typhoid fever. She passed away at just two years old, her small body exhausted by the disease11. Now treatable with antibiotics, typhoid is a highly contagious bacterial infection which was very common at the time and especially prevalent in areas with poor sanitation or limited access to clean water. The family buried Annie on 5 January 1888 at St Andrew’s Church in Helpringham12, where they were now living on the Green near the Methodist Chapel. It was a loss they would carry with them for the rest of their lives.

A Life on the Railway

By the late 1880s, Sam had left agricultural work for the railways, seeking steadier employment. The Helpringham Station opened in 188213 and he found work as a platelayer14, inspecting and maintaining the tracks. The work must certainly have suited him better as he stayed in the same job for the next 40 years. He would however have spent long, arduous hours walking the line with a gang of men, replacing worn out rails or rotten sleepers, levelling the tracks, weeding and clearing drains15. It was hard work, poorly paid and a job with little opportunity for advancement (“the most neglected man in the service”). Sam however was clearly industrious and earned a promotion to foreman in later years16.

Another downside of railway work was the risk to life and limb. It was not uncommon for platelayers to be accidentally struck by trains, often with fatal consequences. In one incident of the time, a careless worker on the Great Northern Railway was waving to a coal train when he got hit by a passenger express coming the other direction. He was completely decapitated, his head later being found 30 yards away from his body17. Although Sam may have avoided serious injury, he almost certainly knew some who were less lucky and was himself involved in a distressing incident of another kind later in his career.

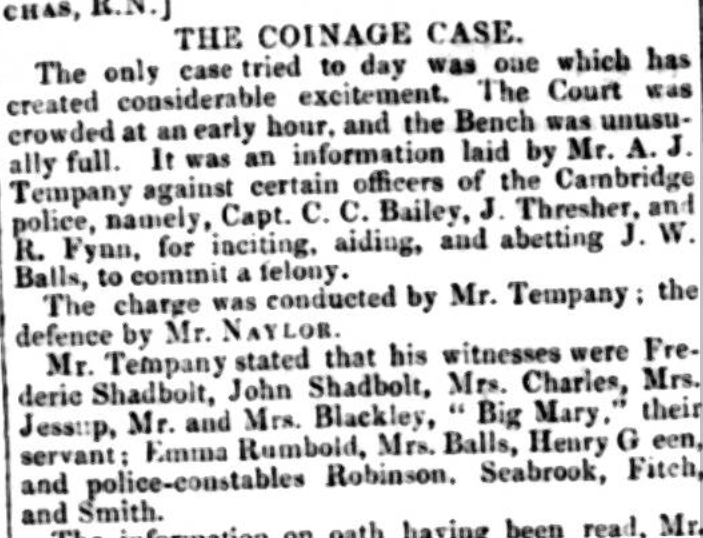

Around 8.30 on one damp January morning, Sam was at work about half a mile from Helpringham station. He noticed something white in the ditch by the side of the line and on closer inspection discovered a small bundle. At first sight it appeared to be clothing but Sam was horrified to find that the parcel was in fact the body of a baby boy wrapped in old bed quilting. He took the body to the local police who concluded that the child had been born very recently and likely died before being thrown from a fast train the previous evening18.

The harrowing sight would have stuck in the memory for anyone, but possibly more so for Sam who had a particular fondness for children. He delighted in his role as class leader at the Methodist Sunday School and his affection for his students was certainly reciprocated19.

Building a Home and a Community

By 1893, the Mattocks’ family was complete with the birth of their second son, Samuel Jr. Around the same time, Sarah’s elderly mother, Jane, moved in with them at Rose Cottage20, where she remained until her passing in 190321.

As their children grew, life carried them beyond Helpringham. By 1901, 18-year-old Charles had moved to Sheffield, finding work in the steel industry and lodging with his cousin, William, the eldest son of Sam’s brother James22. Clara remained at home, working as a dressmaker, but her trips to visit Charles would soon lead her to meet her future husband, Charles Edward Ball (known as Charlie). One of Samuel Jr’s first jobs was with the GN & GE Railway in Lincolnshire23, a position he perhaps secured through his father’s contacts at the company. He later worked as a goods clerk at Misterton Station near Doncaster24.

Over the years, all three surviving Mattock children married—first Charles to Cecilia in 190625, then Clara to Charlie in 191026, and finally Samuel to Ethel in 1919. One can imagine Sam exchanging stories with Charlie’s father, Charles Ball Sr, who also worked on the railway27. It must have been a proud moment for Sam and Sarah to witness each of their children build their own lives and families.

A Sudden Loss

With their children grown, Sam and Sarah remained together at Rose Cottage, their days filled with work, church, and simple pleasures. They had lived there from at least 1910 when they rented the property from elderly estate owner and local dignitary Robert Ellis Watling28. Sam maintained a large allotment near the railway and Sarah took pride in cooking and preserving food29.

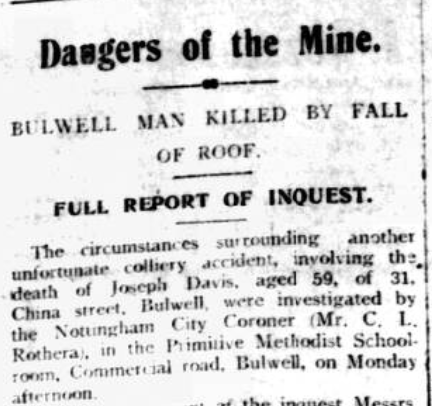

Then, on a chilly afternoon on 9 November 1922, tragedy struck. Sam, at 64, was at work as usual but mentioned feeling unwell. Determined to carry on, he continued his duties until mid-afternoon. As he walked toward the station-yard, he suddenly collapsed. By the time his colleagues reached him, he was gone—his heart had failed. His death was so sudden that an inquest was held the next day. The news sent shockwaves through Helpringham, with local papers reporting that “quite a gloom was cast over the village.”. The funeral service was held at the Primitive Methodist Chapel the following Monday and was largely attended by many friends and family. Old scholars of the Sunday School lined the cemetery path as their “dear Superintendent” was laid to rest30.

Life as a widow

Sarah lived on for 27 years after Sam’s passing. She remained at Rose Cottage, now joined by Clara and her husband Charlie Ball, along with their sons, Ted and Ron who called her ‘Gran’. With Charlie’s health declining, the couple purchased the cottage from Sarah’s landlord, ensuring the family home stayed in their hands. Mother and daughter kept busy growing vegetables, preserving fruit, and cooking together, while the boys attended Donington Grammar School31.

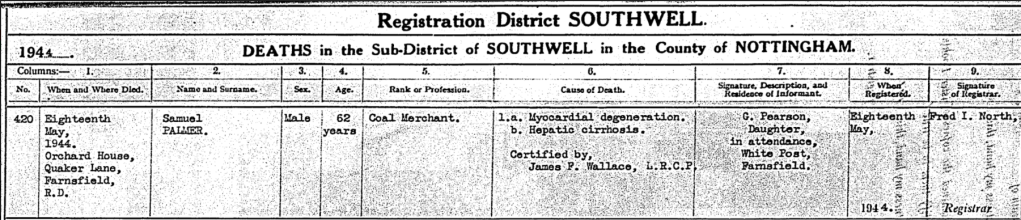

However, tragedy struck again in 1944. Amidst the turmoil of World War II, Charlie Mattock’s wife, Cecilia, took her own life in Helpringham Beck32. Her coat, shoes, hat, and spectacles were neatly arranged on the bank. She had long suffered from depression and had spent time in a mental hospital. Her loss was another painful chapter in the family’s history.

Sarah, now in her eighties, lived to see the end of the war. She passed away on 1 September 1949, aged 86, from heart disease33. She was laid to rest beside Sam in a double plot at the High Street cemetery in Helpringham—a final reunion after decades apart.

A Lasting Legacy

Sam and Sarah’s story is one of resilience, love, and service. From a hurried young marriage to a lifetime of community devotion, they faced their share of struggles but left behind a family deeply rooted in the values they held dear. Their legacy continues in the generations that followed, woven into the history of Helpringham and beyond.

1 Grantham Journal, 2 Dec 1894

2 Sleaford Gazette, 18 Nov 1922

3 1871 census, Heckington, household of Jane Warrington

4 Marriage certificate of Samuel Mattock and Sarah Ann Warrington

5 Stamford Mercury, 23 Mar 1866

6 1871 census, Holbeach, household of William Mattock

7 Avoiding Attention? Assessing the Reasons for Register Office Weddings in Victorian England and Wales. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14631180.2023.2205736#d1e109

8 Marriage certificate, ibid.

9 1881 census, Heckington, household of Jane Warrington

10 1891 census, Helpringham, household of Samuel Mattock

11 Death register entry for Annie Mattock

12 Lincolnshire parish registers, 1538-1911

13 Wikipedia, Helpringham railway station – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Helpringham_railway_station

14 1891 census, ibid.

15 The Dirt of the Victorian Railway Industry – The Platelayers, https://turniprail.blogspot.com/2010/11/dirt-of-victorian-railway-industry.html?m=1

16 Grantham Journal, 1 Feb 1913

17 Nottinghamshire Guardian, 16 Dec 1893

18 Grantham Journal and Sleaford Gazette, 1 Feb 1913

19 Sleaford Gazette, 18 Nov 1922

20 1901 census, Helpringham, household of Samuel Mattock

21 Death index entry for Jane Warrington

22 1901 census, Attercliffe cum Darnall, household of Sarah Ann Walker

23 1911 census, Cowbit nr Spalding, household of Middleton Pinder

24 1921 census, Misterton, household of Samuel Mattock

25 Marriage index entry for Charles Mattock

26 Marriage certificate of Charles Edward Ball and Clara Jane Mattock

27 1901 census, Attercliffe cum Darnall, household of Charles Ball

28 Email from Julie Close (Helpringham History Society) to Jaine Burton

29 Letter from Allen Mattock, 10 May 2010

30 Louth Standard 25 Nov 1922 and Sleaford Gazette 18 Nov 1922

31 Interview with Dina Maclean, 6 Mar 2010

32 Sleaford Gazette, 2 Jun 1944

33 Death certificate of Sarah Ann Mattock

Research Notes

We can’t know for sure why they chose to marry at the Register Office but there are three possible reasons: to keep the wedding private; practical considerations of location, cost and speed; or ideological preferences. All of these may be factors.

The first three children were baptised at Heckington parish church but there is no record of Samuel being baptised in the parish registers. It could be that their Methodism had fully taken over by then. It’s interesting that Clara’s marriage took place at the Anglican church of St Andrew’s, but perhaps this was her husband’s influence.

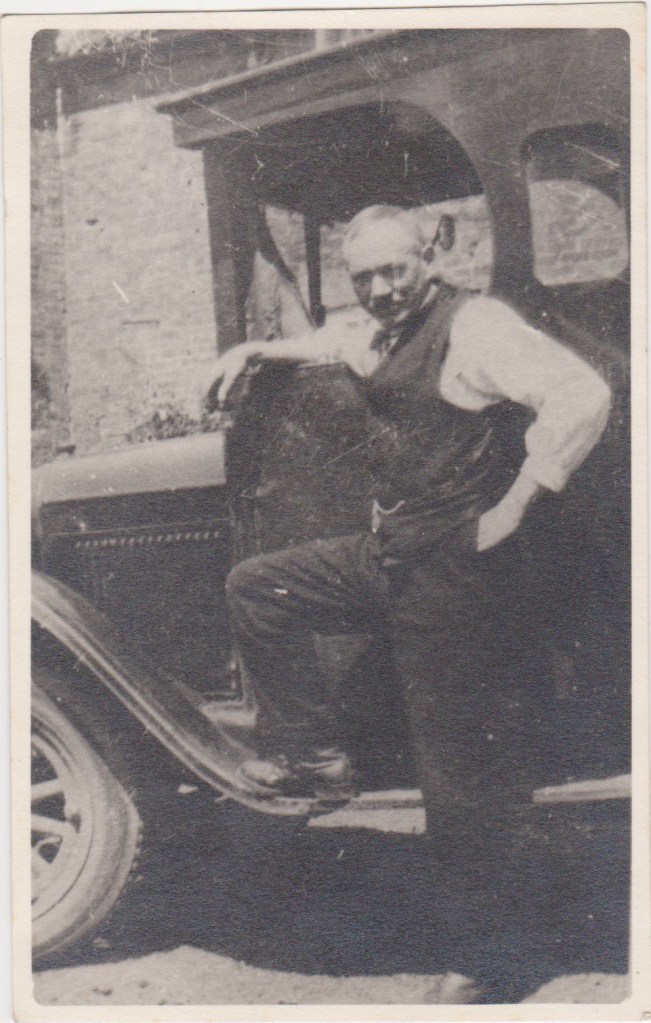

I’m not sure exactly when they moved into Rose Cottage but tax records held by Julie at the Helpringham History Society showed it was at least 1910. The photo in front of the coal shed looks to have been taken around 1905, given Samuel Jr’s age. Granny said she had to fetch coal from that shed when she stayed there, suggesting that it was taken at Rose Cottage, but it could easily be a similar shed at a previous property.

It would be worth investigating if any records exist for the parish council, Sunday School, Methodist Chapel, temperance league or GN & GE Railway. More research would be valuable on the lives of Charlie and Samuel Mattock Jr.