Archibald McLean (1830-1915) lived within a few miles of his birthplace for over 70 years and did the same job as his father and grandfather before him. Strange then, you might think, that he should end his life over 3000 miles away in the Appalachian mountains of America.

Born in the Dunfermline area of Fife, Scotland in the winter of 1830, Archibald was the 7th child of Thomas and Gomry McLean[1]. They lived in the small mining village of Lochgelly with 4 daughters and a son, having lost another son also called Archibald in recent years. Lochgelly consisted of only a few scattered houses, mostly thatched, and was a pleasant place, quiet except for the clatter of a handloom[2].

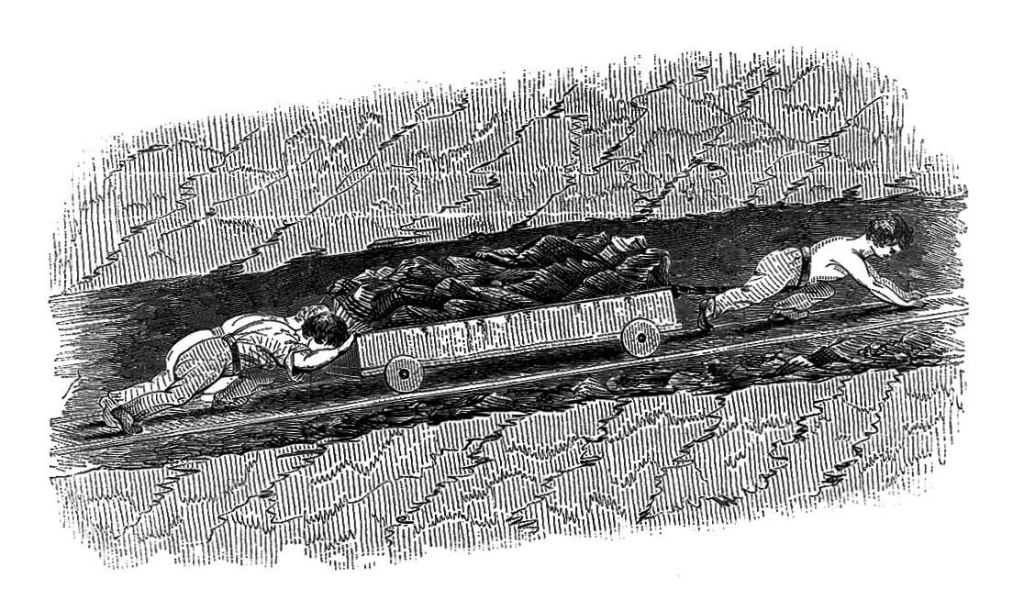

His father, Thomas, was a coal miner, as the McLean’s had been for generations before, and by the time he was 10, Archibald and his older brother Alexander were accompanying him down the mine for up to 12 hours a day. They would work together in near darkness, probably naked due to the heat, ‘howking’ coal out with pickaxes which their sisters Christina and Montgomerie would then pull on heavy carts through low tunnels up to the surface[3]. Unlike in the west of Scotland, where up to half of the workforce were Irish immigrants, the coalfields around Fife were still mainly worked by traditional Scottish mining families like the McLeans and there would have been little question that Thomas’ sons followed him into the pits, possibly starting work as young as 6 years of age[4].

Mines in this period were cramped, poorly ventilated and highly dangerous with accidents and deaths commonplace – the most frequent causes being roof falls and gas explosions[5]. An 1842 investigation into child labour in some of the collieries in the area reported numerous injuries to children including a 12-year old Mary McLean (possibly a cousin of Archibald) whose legs were crushed by a 300kg coal cart[6].

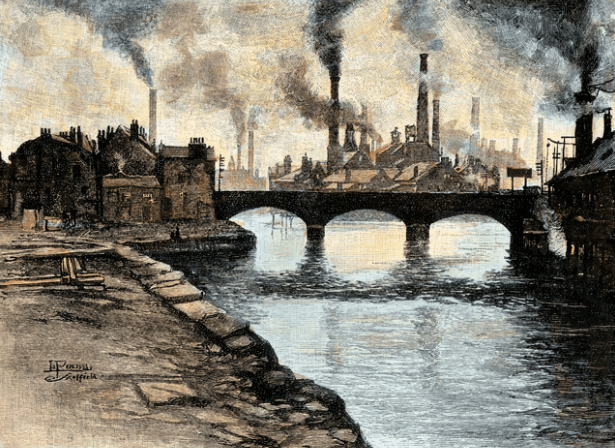

The railway arrived in Lochgelly in 1849, which marked the start of a dramatic period of expansion, with many more pits opening up in and around town[7]. The McLean family had moved to the nearby village of Crossgates by 1851, with Archibald (now 20) still mining with his father (61) and his younger brother Thomas (18)[8]. His younger sisters, Helen, Elizabeth and Grace were spared the gruelling work and were able to stay at home with their mother since legal reforms had outlawed women from working in the mines a few years earlier. They were likely living in housing rented from one of the large coal companies operating in the area, which were often low-ceilinged, badly lit and damp, sometimes with the stench of open drains not far from the door[9].

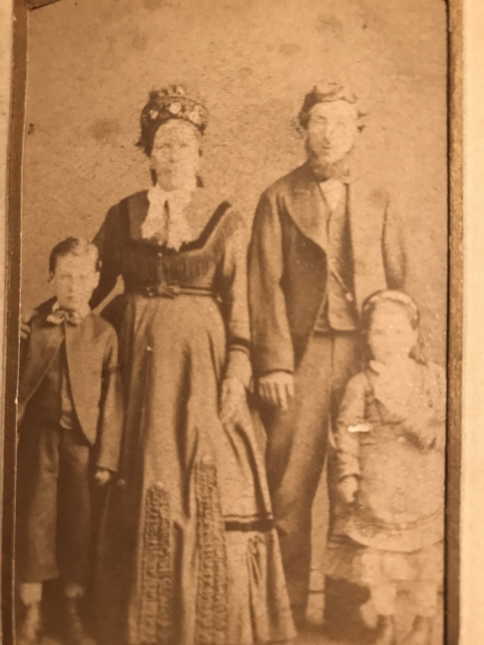

In January of 1852, aged 22, Archibald married Jessie Thomson, the daughter of a miner from a poor family in Milesmark[10], around 6 miles away on the other side of Dunfermline. They moved in together in her home village, which was small with only a handful of cottages and collier’s houses, a school and a pub[11]. Over the next 13 years they had 7 children together until Jessie sadly died of heart disease at the age of 38 in 1866, 2 months after giving birth to their 4th son[12].

Archibald remarried later that year to Rachel Sneddon, who herself had been widowed and they lived together on Cottage Row in Milesmark for 36 years, having 2 further children together[13].

A newspaper correspondent, writing in 1875, described Cottage Row thus:

“[The houses] are uniform in style and internal arrangement – large rooms and kitchens, with lofty ceilings, lumpy stone floors, and ample window space on both sides … They are very well furnished, several of the rooms having tester beds with damask curtains, engravings on the walls, and on the tables family Bibles and other books, showing that the people do not belong to the lower class of miners.”

The Old “Fitpaths” and Streets of Dunfermline (Dunfermline Journal 27 Feb 1875)

It would seem as if Archibald’s skill and experience in the mines had allowed him to provide a reasonable standard of living for him and his family. The same perhaps could not be said though for two of his young sons-in-law, Thomas Beveridge and William Hynd, who had married his daughters Montgomery and Maggie respectively. They were also both coal miners but during the severe economic depression of the 1880s they had begun to look further afield for better opportunities. The decisive move came in 1886 when Beveridge packed up and made his way to Glasgow to board a transatlantic steamer bound for Philadelphia[14]. He, like thousands of others from across Europe, had been enticed to start a new life in America with the promise of land to farm. First though he would have to survive the wretched conditions as a ‘steerage’ passenger below deck where the minimal space, insufficient food, general filth and stench made the voyage “almost unendurable”[15]. Not the ideal beginning to a new dream life.

Unperturbed by (or perhaps unaware of) the journey to come, Montgomery followed a few months later with their 4 children[16] and it wasn’t long before Maggie and William Hynd were also travelling over to visit them[17] and see what life was like in the hills of Clearfield County, Pennsylvania, 250 miles west of New York. The Hynds returned to Dunfermline after a year, with a new baby Archibald in tow[18], no doubt excited to introduce him to his grandfather and tell the old man all about their adventure.

Archibald meanwhile continued doing what he knew best, working down the mine, perhaps at the extensive Elgin and Wellwood Colliery near Milesmark, and when he finally retired he had worked in the pits around Dunfermline for more than 50 years. The work had changed dramatically in that time from a small family group toiling with hand tools, to a more industrial, mechanised operation, albeit still with a multitude of dangers for the colliers.

When his second wife Rachel died in 1902 at the age of 75[19], Archibald moved in briefly with his son Archibald Jr and his family, but reportedly did not get on well with his daughter-in-law[20]. It was thus in 1904 that he decided to leave behind all that was familiar and go with Maggie and her children as they set off back to Pennsylvania to join William, who had returned, this time permanently, the year before. This couldn’t have been an easy decision for Archibald and it perhaps took much persuasion from Maggie for him to go with her.

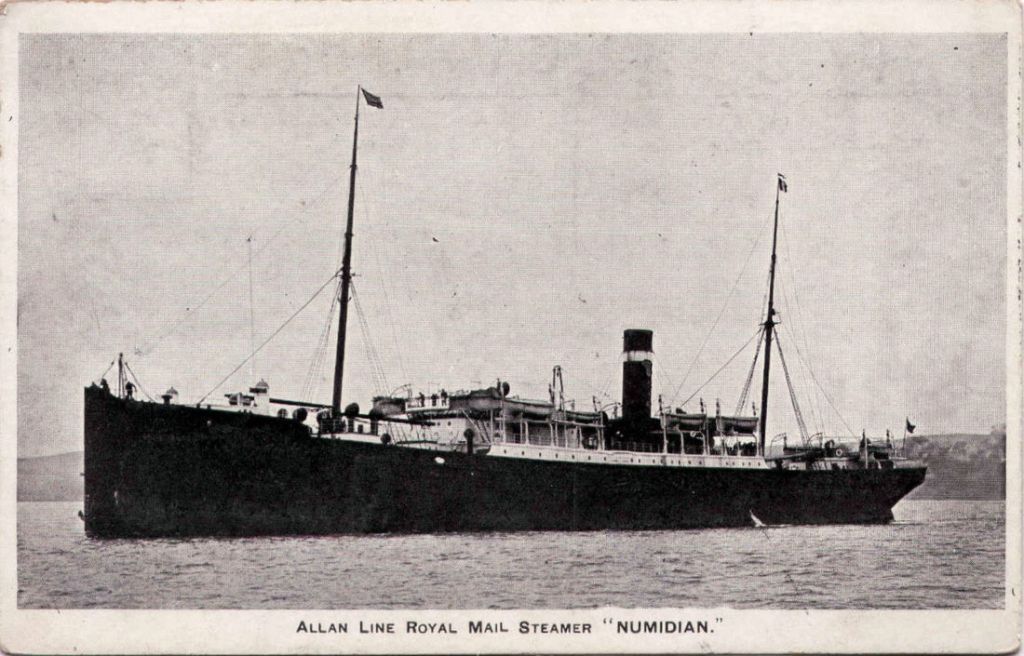

After saying a no doubt tearful goodbye to his family in Fife, the elderly Archibald made the 16-day trip from Glasgow to New York on the steamship the “SS Numidian”, travelling in second-class accommodation[21]. This would have been relative luxury compared to those on the lower steerage decks, although sailing across the stormy north Atlantic in February may still have been stomach-churning for the inexperienced traveller.

There must have been great scenes when Montgomery was reunited with her father after nearly 20 years in the States, and any misgivings he had about his new home may have been tempered by the familiar sight of coalfields dotting the Pennsylvanian landscape.

Having arrived safely in Clearfield County, Archibald lived there on the farm, amongst an extended family, until he died of heart failure on 27 Feb 1915 at the age of 85[22]. He was buried in Summit Hill Cemetery and was described in his obituary as “a Christian gentleman with a kind and gentle disposition that made him respected wherever known”[23]. He died a grandfather of 35 and great grandfather of 18.

References

[1] Old Parish Registers Births, Dunfermline

[2] “Bygone Life in Lochgelly: Stray Memories of an Old Miner”, http://www.fifepits.co.uk/starter/stories/stor_4.htm

[3] 1841 census of Scotland

[4] The Mineworkers, Robert Duncan, Birlinn 2005

[5] ibid.

[6] Collieries in the Western District of Fife, Childrens Employment Commission 1842, http://www.scottishmining.co.uk/89.html

[7] Lochgelly Feature Page on Undiscovered Scotland, https://www.undiscoveredscotland.co.uk/cowdenbeath/lochgelly/index.html

[8] 1851 census of Scotland

[9] Notes on Miners’ Houses Part XII, http://www.scottishmining.co.uk/413.html

[10] Old Parish Registers Marriages, Dunfermline

[11] Fife and Kinross-shire OS Name Books, 1853-1855, https://scotlandsplaces.gov.uk/digital-volumes/ordnance-survey-name-books/fife-and-kinross-shire-os-name-books-1853-1855/fife-and-kinross-shire-volume-128/71

[12] Scotland Statutory Death register

[13] Censuses of Scotland, 1871-1901

[14] Pennsylvania, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists, 1800-1962

[15] “Steerage Conditions,” in Reports of the Immigration Commission, Volume 37. 1911.

[16] New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820-1957

[17] Pennsylvania, Philadelphia Passenger Lists, 1800-1948

[18] UK Incoming Passenger Lists, 1878-1960

[19] Scotland Statutory Register Deaths Index, 1855-1956

[20] Recording of conversation with Mary Maclean, c.1978

[21] New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820-1957

[22] Death certificate of Archibald McLean

[23] Obituary of Archibald McLain (sic)