My grandma never knew her husband Les’ maternal grandfather and all she could tell me about him was that he owned several lorries in Farnsfield, Nottinghamshire and that he was an alcoholic. “I don’t even know what it was that he drunk”, she said. “It’s usually spirits, isn’t it? But I’ve no idea.”

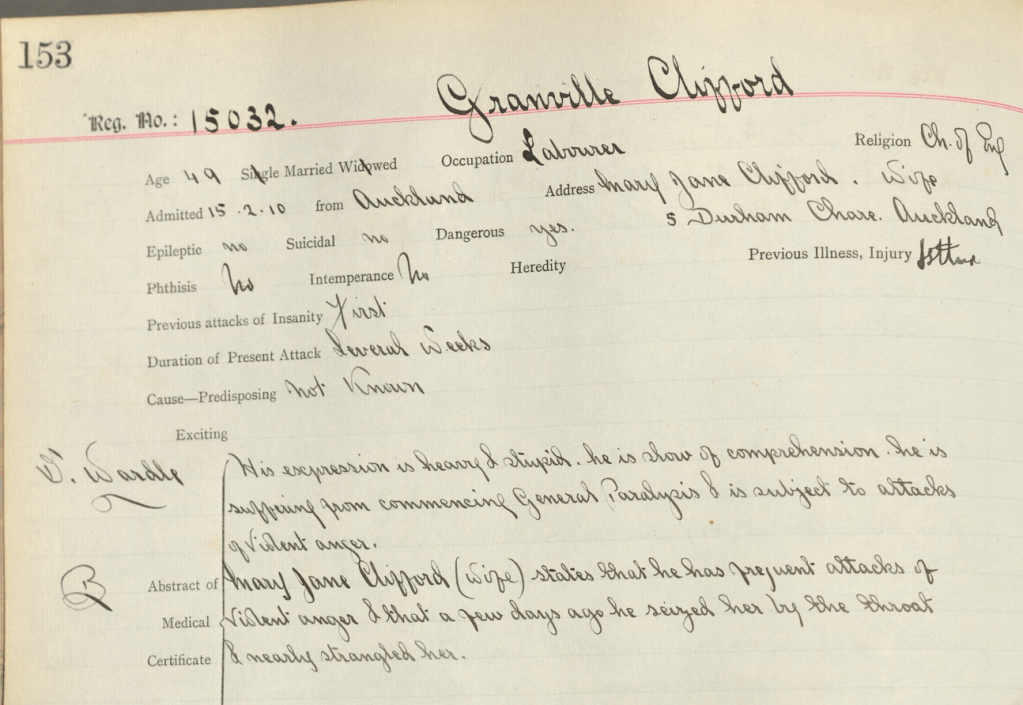

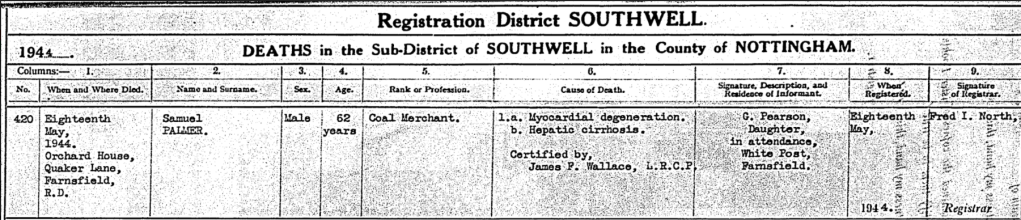

“The alcoholic”, as my mum referred to him, was called Sam Palmer (although that wasn’t his birth name) and he died from liver cirrhosis[1], a tell-tale sign of alcohol abuse, in May 1944, a few weeks before the Allied troops landed on the beaches of Normandy. Alcoholism is usually caused by a combination of societal and family factors, and can be triggered by stressful events[2]. The life of Samuel Palmer (1882-1944) provides an unfortunate case study of how circumstances, often outside of our control, can play a crucial, and sometimes damaging, part in our mental health.

To appreciate the full story we need to go back to the year before Sam was born. In 1881, 50-year-old framework knitter Samuel Hallam was living with his 23-year-old housekeeper Elizabeth on a row of knitter’s cottages in the large, straggling village of Woodborough, 8 miles north-east of Nottingham[3]. His wife Jane had died 8 years previously[4], and the young Elizabeth, daughter of Hallam’s friend Thomas Palmer was an attractive prospect for the aging widower. They started a relationship and had a daughter Rebecca, out of wedlock, followed by a son Samuel who died after only a few weeks[5]. Their third illegitimate child, another son and our subject, born in February of 1882, was also baptised Samuel Hallam[6] although he would later opt for his mother’s surname.

Over the first 10 years of young Sam’s life, he and his elder sister Rebecca suffered considerable trauma. They saw two more sisters die as babies[7] and although a brother, Harry, would survive, by 1891 their father was ill and unable to work to support the family. Things got so bad that the three children, along with their ailing father, ended up in Basford workhouse, while their mother went to stay with her sister’s family[8].

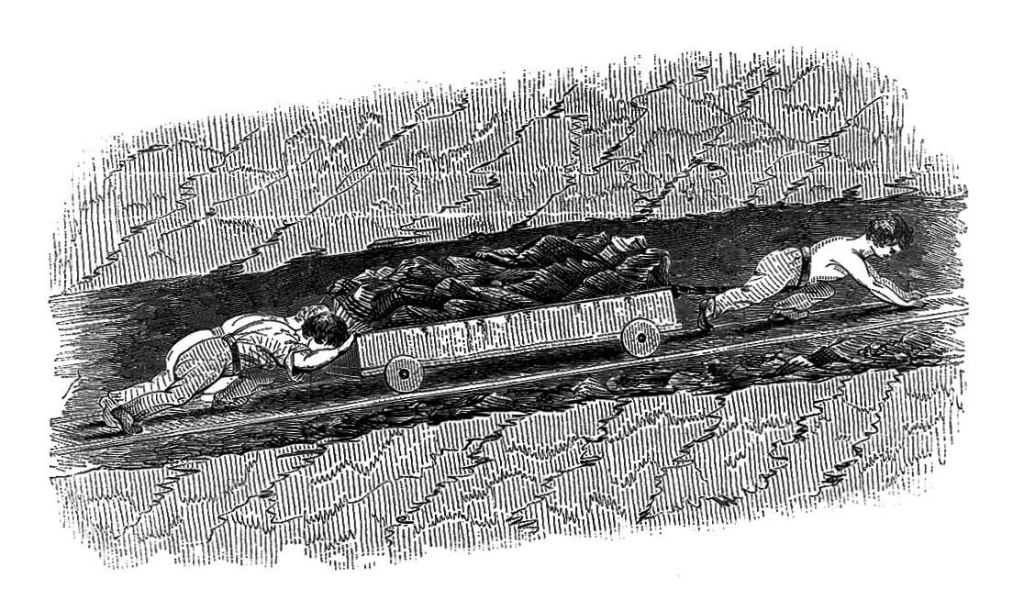

Although the children received some schooling while they were in the workhouse, and were taken on occasional outings (including a trip to Skegness[9]), they were separated from their parents (and probably each other) and must have been scared and lonely as they first tried to sleep at night in the cramped dormitories. Flogging of young boys for minor infractions was common practice in some workhouses of the time, as were reports of systematic child abuse by depraved nurses[10]. To make matters worse their father died during their time inside[11], leaving the Palmer children (as they were now known) with only each other for comfort. A Poor Law Commissioner inspecting Basford in 1891 did consider the conditions there satisfactory and reported “favourably of the food and treatment, but made suggestions with regard to bathing and amusements”[12], so perhaps Sam was relatively well looked after, albeit a little bored and grubby. Some workhouses gave the boys half a pint of beer with their dinner and supper each day[13], so maybe this was where Sam first got a taste for it.

When Sam got out of the workhouse (possibly aged 14 when he was deemed old enough to enter employment) he worked first as a wagoner[14], driving horses on a farm, and later moved into the city to work in one of the many coal mines[15]. It was here that he met Nelly Davis, a lace mender from Bulwell, and they married in 1905[16] when Nelly was several months pregnant with their first child (a daughter, Gladys). Life seemed to be improving for Sam as they lived first with Nelly’s family and then moved into a small house of their own on the same street.

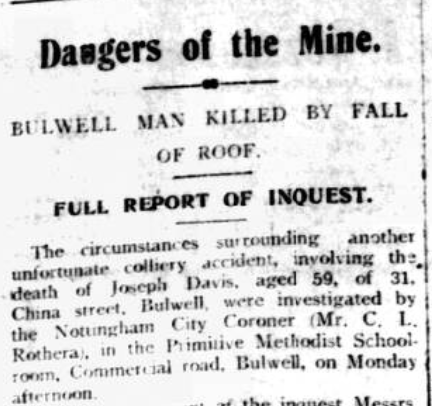

In 1913 however, tragedy struck. Nelly’s father Joseph, also a coal miner, whom Sam knew well and perhaps worked with, was killed in an accident late at night in the pit. Despite being an experienced collier, and all necessary precautions being taken, a part of the roof had fallen on him while he reached underneath[17]. Nelly and her mother must have been devastated, and Sam too who would have to keep going down into the depths to work with the thoughts of what happened to Joseph surely playing on his mind.

Newspaper image © The British Library Board. All rights reserved. With thanks to The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

Perhaps not surprising then that Sam and Nelly, who now had a second daughter, left the city shortly after. Sam got a job at Rufford Colliery, and the family looked to be moving on from their loss as they moved into a nice cottage with a large garden in Farnsfield called Orchard House and were further blessed with a son[18].

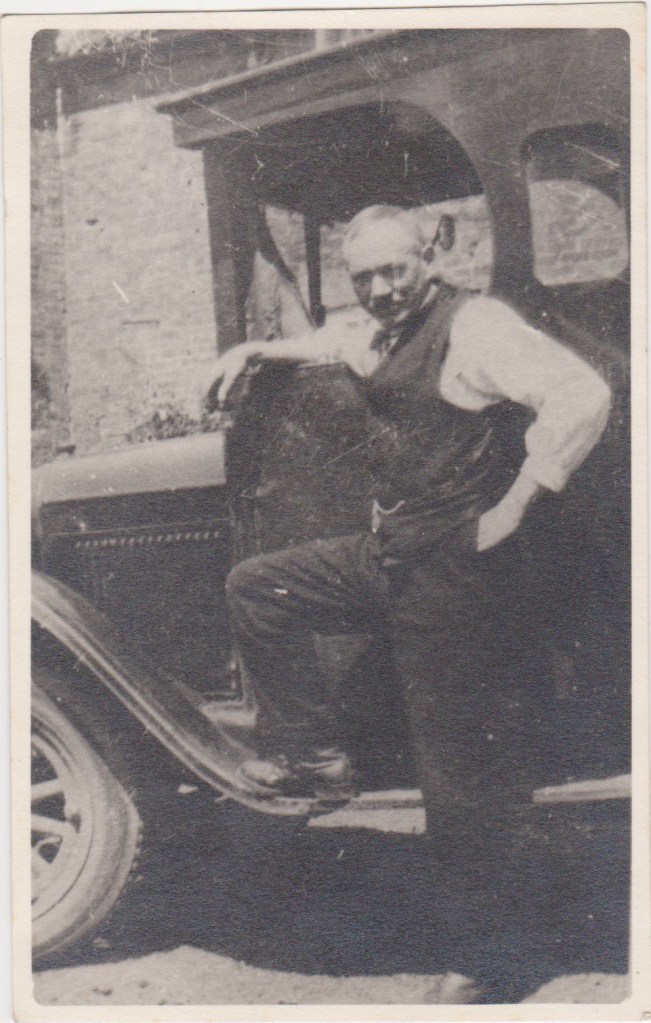

Around this time, Sam was making friends in the local community, playing cricket[19] and becoming the president of the ‘Farnsfield and Edingley Pig Club’. At the club’s annual dinner at the Plough Inn in March 1924, Sam was in charge of proceedings and contributed to the general merriment with songs and poetry recitals[20]. Later that same week, daughter Nelly and son Samuel Gilbert (known as ‘Sonny’) were receiving prizes at the church schoolroom. The packed audience, no doubt including a very proud Sam and Nelly, watched the children perform sketches from Peter Pan, Alice in Wonderland and a Midsummer Night’s Dream[21]. With financial help from his brother Harry, Sam was also able to give up mining and start his own business as a haulier[22], taking advantage of the growing need for heavy goods transportation in the post-war housing boom[23].

As with the rest of Sam’s life though, misfortune was never far away. In January 1926, their only son Sonny, who had suffered for a long time with a spinal complaint, took ill and died a few days later[24]. He was just 9 years old. If Sam had managed to keep a lid on his drinking until then, was this the moment that everything became too much? It must have been unbearable, sitting in the cold church, seeing the sprays of flowers sent by Sonny’s schoolmates, trying to stay strong for Nelly and the girls.

Sam was a keen gardener, and in the months and years that followed Sonny’s death, he won many prizes for his fruit and vegetables at local horticultural shows (at one he was commended for his “exceptional” onions)[25]. His young daughter Nelly also had success growing wildflowers – working outside together at Orchard House and tending to their garden perhaps gave them all some solace in trying times. He continued to work as a haulage contractor[26] and play cricket for Hargreave Park on summer weekends.

Evidently Sam continued to struggle with his drinking however, and there must surely have been occasions when he was driving on the roads around Farnsfield with a mind clouded by ale, or something stronger. Although there was no legal drink driving limit until 1967, Sam could still have lost his license for 12 months, or even been sent to prison, for being caught drunk in charge of a vehicle[27]. The consequences for his business would have been disastrous.

So although Sam may have seemed like the life of the party when he was singing songs into the night at cricket club suppers at the Plough[28], underneath he never quite escaped his troubled upbringing and a life punctuated by tragedy. He died aged 62 on May 18th 1944 when his heart finally gave in[29].

References

[1] Death certificate of Samuel Palmer

[2] Alcohol dependence and withdrawal, drinkaware, https://www.drinkaware.co.uk/facts/health-effects-of-alcohol/mental-health/alcohol-dependence

[3] 1881 Census of England & Wales

[4] England & Wales, Civil Registration Death Index, 1837-1915

[5] Nottinghamshire Baptisms, Nottinghamshire Family History Society

[6] ibid.

[7] ibid.

[8] 1891 Census of England & Wales

[9] Nottingham Evening Post, 14 July 1891

[10] Higginbotham, Peter “Children in the Workhouse”, https://www.workhouses.org.uk/education/

[11] England & Wales, FreeBMD Death Index: 1837-1915

[12] Hucknall Morning Star & Advertiser, 4 December 1891

[13] Higginbotham, Peter “Workhouse Food”, https://www.workhouses.org.uk/life/food/

[14] 1901 Census of England & Wales

[15] 1911 Census of England & Wales

[16] Marriage certificate of Samuel Palmer & Nelly Davis

[17] Beeston Gazette & Echo, 1 November 1913

[18] 1921 Census of England & Wales

[19] Newark Herald, various reports from 1922 to 1929

[20] Newark Herald, 8 March 1924

[21] ibid.

[22] Correspondence with Sue Palmer, 2011

[23] The history of haulage and road transport in the UK, https://www.snapacc.com/blog/0021-The-history-of-haulage-and-road-transport-in-the-UK/

[24] Newark Herald, 30 Jan 1926

[25] Newark Herald, various reports from 1925 to 1929

[26] Marriage certificate of Gladys Palmer and Alfred Pearson

[27] A History of Drink Driving & Motoring Laws in the UK, https://www.drinkdriving.org/drink_driving_information_uklawhistory.php

[28] Newark Herald, 2 November 1929

[29] Death certificate of Samuel Palmer