My next subject is on my father’s side of the family and is the first in our history to be born with the name ‘Ball’ (more on that another time). His story is one of a working class Yorkshireman whose determination and astute business sense brought financial success. But ultimately it was his job that killed him.

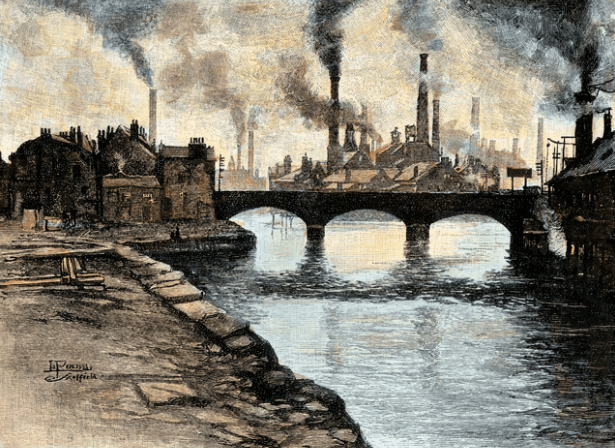

Charles Edward Ball (1875-1934) was born in Attercliffe in the “East End” of Sheffield, the eldest child of a railway worker and his teenage wife[1]. Attercliffe was the largest area of Sheffield at the time, owing to the extensive manufacturing industry which had built up around the nearby railway and canal, and was at the heart of the city’s Industrial Revolution[2]. One writer described the area at the time as “masses of buildings, from the tops of which issue fire, and smoke, and steam, which cloud the whole scene, however bright the sunshine.”[3]

As a young man Charles looked set to follow his father into manual labour and worked first as an apprentice wagon wheel maker, aged 15[4], and later as an iron worker[5]. This was hard physical work but Charles was in good shape. He competed in foot races, specialising in the quarter and half mile distances, and in his peak was beating the local competition and running the 440-yard dash in around 52 seconds (only a few seconds off world record pace)[6]. Sheffield was world-renowned for athletics in the Victorian era and these races were prestigious affairs with a large number of entrants, thousands of spectators and prize money up to £10 per race, which would have equated to around a month’s wages for Charles at the time[7].

One can imagine Charles being careful with his money and perhaps saving his winnings for a rainy day, as although metalworking was a skilled job, employment was inconsistent and wages often varied on a sliding scale linked to the prevailing market prices for iron and steel[8].

A turning point in Charles’ life came in his mid-twenties when he met a young ostler’s daughter by the name of Emily Moore. Emily was living with her grandfather, George Carr Jessop, in Rotherham at the turn of the century[9]. Jessop was a seed and corn merchant and had previously been a grocer in Attercliffe and a Baptist deacon[10]. Charles fell for Emily and they married in October 1901[11], at which point he decided to pursue a more stable living, perhaps with the influence of Jessop who was protective of his granddaughter.

He took up work at the seed shop and became a partner with the aging Jessop. By 1904 the shop was named ‘Jessop & Ball’ and was situated between a hosiers and a paint & wallpaper seller within the Market Hall in Rotherham[12]. They sold all manner of seeds for bird food, gardens and flowers, as well as other products such as dog food[13]. They also sponsored local pigeon racing[14] and Charles showed his competitive nature again by winning prizes for his poultry in the “Fur and Feather Fanciers” show[15].

Charles was probably already in charge of the day-to-day running of the shop when George Jessop died shortly after[16], but continued trading under the Jessop & Ball name until tragedy struck a few years later. Emily took ill and died suddenly of appendicitis in 1908[17]. The couple had been married 6 years, without seemingly producing any children.

It wasn’t long however before Charles fell in love again. Clara Mattock, a dressmaker from Lincolnshire, came to Sheffield regularly to visit her brother Charlie who worked in the steel industry[18]. It may have been on one such visit that her path crossed with Charles and they got together and married in 1910. The local paper reported the occasion as a “pretty wedding” and that afterwards the happy couple proceeded by train straight to their honeymoon in Scarborough.[19]

Charles and Clara would stay in Rotherham for another 15 years, raising 2 sons, Ted and Ron. The seed business, now run by Charles alone, went from strength to strength and the family were able to move to a larger property on the outskirts of town[20]. The transition from skilled working class to the respectable lower middle class was complete. But Charles’ health was deteriorating. Years of moving and processing seeds for the shop had exposed him to harmful grain dust which when inhaled can cause serious respiratory illness[21].

In 1926, at the age of 51, he was forced to sell up and move his young family to Clara’s home village of Helpringham. They lived at the beautiful Rose Cottage which Clara’s widowed mother was renting and later used their considerable savings to buy the cottage themselves. As Charles’ condition worsened they built a special wooden outbuilding for him to sleep in, with big windows to let in plenty of fresh air[22].

After a long and painful illness, Charles died in 1934 from heart disease caused by his chronic bronchitis[23]. Described as a strict father by his sons and still proud of his working class roots (he didn’t want them to go to university), Charles had worked hard to change the fortunes of the Ball family and he left Clara, his “dear wife”, with almost £14000 which would be worth at least £1 million today[24][25].

References

[1] 1881 census of England & Wales

[2] White’s Directory of Sheffield, 1879

[3] Burngreave Voices, Sheffield Galleries & Museums Trust, https://www.museums-sheffield.org.uk/project-archive/burngreave-voices/housesWorkers.html

[4] 1891 census of England & Wales

[5] 1901 census of England & Wales

[6] Sheffield Independent, 2 July & 21 August 1895. Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 28 May 1896

[7] Wages in the United Kingdom in the 19th century, Arthur Bowley, 1900

[8] Evans, A. D. (1909). An Iron Trade Sliding Scale. The Economic Journal, 19(73), 122–133. https://doi.org/10.2307/2220530

[9] 1901 census of England & Wales

[10] Malcolm Bull’s Calderdale Companion, https://freepages.rootsweb.com/~calderdalecompanion/history/j.html

[11] Marriage certificate of Charles Edward Ball and Emily Moore

[12] White’s Directory of Sheffield & Rotherham, 1905

[13] Photo of Charles Edward Ball outside his seed shop

[14] Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 15 Aug 1904

[15] Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 5 Nov 1909

[16] UK and Ireland, Find a Grave Index, 1300s-Current

[17] Death certificate of Emily Ball

[18] Recording of conversation with Dina Maclean, 2010

[19] Sleaford Gazette, 17 Sep 1910

[20] 1921 census of England & Wales

[21] 1988 OSHA PEL Project – Grain Dust, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/pel88/graindst.html

[22] Recording of conversation with Dina Maclean, 2010

[23] Death certificate of Charles Edward Ball

[24] Will and Grant of Probate of Charles Edward Ball

[25] Purchasing Power of British Pounds from 1270 to Present, MeasuringWorth.com, https://www.measuringworth.com/calculators/ppoweruk/