William Maddock (later Mattock) and Keziah Jackson spent their entire lives in the rural Lincolnshire fens, raising 11 children while struggling to make ends meet. William was born in Dowsdale near Crowland[1], but his life changed dramatically when his father died when he was just 12[2]. Left without a paternal figure, he worked for a grazier named James Whitsed in nearby Postland[3]. William’s duties likely included raising cattle or sheep for market, with food and lodging provided in exchange for his labor. He was one of three servants working for Whitsed and his wife.

Meanwhile, Keziah, nearly three years younger than William, grew up less than two miles away in Whaplode Drove at her parents’ home on Green Bank[4]. Her father, James Jackson, was an agricultural laborer, so it’s likely that William and Keziah crossed paths during their youth in the 1840s, though they didn’t marry until later.

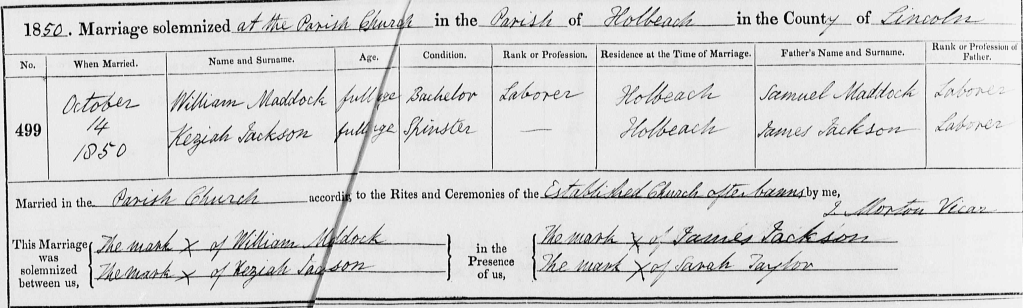

By 1850, they were engaged, and on October 14 of that year, William (23) and Keziah (20), who was already four months pregnant, traveled to the market town of Holbeach. There, they were married at the Church of All Saints by Reverend James Morton[5]. Neither the bride nor the groom could sign their names, so they, along with the witnesses James Jackson (Keziah’s father) and Sarah Taylor, marked the register with an ‘X.’

The couple initially settled in Moulton[6], just a few doors down from Keziah’s parents, where their first son, James, was born in early 1851[7]. Soon, they moved to Holbeach Fen, a place where they would remain for the next four decades. William took up work as a shepherd[8], and the family grew rapidly, adding five more sons—John, William, Samuel, and Charles—and two daughters, Mary and Elizabeth, over the next 11 years[9].

Life in the mid-nineteenth century was hard for a family of their size. Formal schooling did not become widespread until 1870, so the older children—particularly the boys—likely helped with farm work to supplement the family income. Keziah and the older girls took care of the household chores and looked after the younger children. Education was often an afterthought, with reading and writing seen as unnecessary skills for farm work.

Money was tight, and with so many mouths to feed, proper nourishment was difficult to come by. Illnesses, particularly childhood diseases like measles, were common and deadly. Measles, which was typically a mild infection, was one of the leading causes of death for children during this time, and in 1863, it claimed the life of their second eldest child, John. After a long day’s work in the fields, possibly weakened by malnutrition, John fell ill, and despite Keziah’s likely efforts to treat him with tonics and remedies, he died on May 26, 1863, aged just 10[10].

Over the next few years, the Mattocks had four more children—David, Thomas, Jacob, and Ruth. With the addition of each child, making ends meet became increasingly difficult. However, a turning point came in 1870 with the establishment of local education authorities. For the first time, the older children could attend regular school, and Keziah was able to contribute more to the family’s earnings.

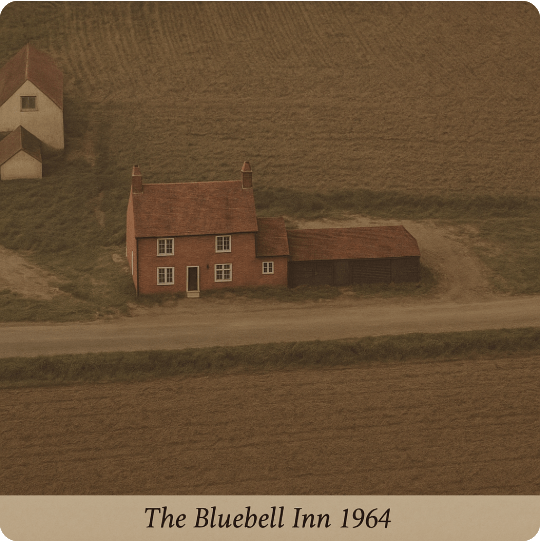

With an agricultural depression beginning to affect the region, William and Keziah, now in their 40s, decided to open a beerhouse. A “beerhouse” was a private home where an “ale wife” could brew and sell beer. They later took over the Bell Inn on Cranesgate in Whaplode, supplementing their income by renting rooms to lodgers. Despite the growing business, William continued working as a farm laborer and kept cows on their four-acre plot of land[11].

Running an inn was far from straightforward. In 1871, the Bell Inn was the site of a dramatic and dangerous event. A man named John Wallace, an Irish harvestman, began causing a disturbance in his room in the early hours of the morning, smashing furniture and throwing it through the window. The other lodgers cowered in fear as a policeman, PC Woodhall, was summoned from Holbeach, four miles away. Wallace, in a violent rage, struck the officer on the head with part of a cast iron fender. Though wounded, PC Woodhall, with the help of some other men, was able to subdue Wallace, who was later declared insane and committed to the County Lunatic Asylum[12].

The Mattocks also faced challenges due to the Licensing Acts, particularly the 1872 Act. This law limited closing hours to 11 pm in rural areas and regulated beer content, even allowing local authorities to ban alcohol altogether. The Act led to protests and near-riots as publicans resisted what they saw as an attack on their livelihoods. William received a caution in 1877[13] after being fined for permitting drunkenness at the Bell[14]. For many in the industry, losing their license would have meant financial ruin, and the annual licensing meeting at the Sessions House in Spalding must have been an intimidating event for someone like William, who could ill afford to lose his business.

In 1884, the Third Reform Act extended the right to vote to men who owned property worth £10 or more, including William. This shift meant that for the first time, he was part of a larger group of rural men who gained the right to participate in national elections.

As the years passed, William and Keziah saw many of their children marry and start families of their own[15], both in the Holbeach area and beyond. The 3 girls all married local farm workers but of their sons only James remained nearby, running an inn in Sutton St. James[16], while the others ventured out in search of work. Jacob, David, and Thomas moved to Yorkshire for industrial work, although David later returned to Whaplode, where he became a farmer. Samuel worked in Heckington and Helpringham before settling in to work on the railways. Charles, and possibly William, emigrated to Ontario, Canada, to continue farming.

By 1891, William, 64, and Keziah, 61, were still running the Bell Inn. Their son Thomas, now 23, had joined them in the family business, while in neighboring properties, their daughter Mary lived with her three children, and their son David had settled nearby with his wife and child.

However, by 1895, the family dynamic had shifted. David had relocated to Attercliffe, Sheffield, in search of work, while Thomas had married and started his own family.

Keziah passed away on February 8, 1897, at the age of 67 after a stroke[17], what was then referred to as “Cerebral Disease, Paralysis.” William, suffering from dementia and unable to care for himself, was admitted to the Holbeach Union Workhouse. He died 10 months later, on December 28, 1897, at the age of 70[18].

[1] Transcript of William’s baptism record in Thorney, Cambs, 21 Jan 1827, “Cambridgeshire Baptisms”, FindMyPast

[2] Index entry for Samuel Maddock, Holbeach, Lincs, 1839, “England & Wales, Civil Registration Death Index, 1837-1915”, Ancestry

[3] 1841 Census entry for James Whitsed, Portland, Crowland parish, HO107/606/13

[4] 1841 Census entry for James Jackson, Green Bank, Whaplode Drove, HO107/612/3

[5] Parish register for Holbeach All Saints, marriage entry for William Maddock & Keziah Jackson, Oct 14 1850

[6] 1851 Census entry for William Mattock, Queen’s Bank, Moulton, HO107/2096

[7] ibid.

[8] 1861 Census entry for William Mattock, St. John’s Road, Holbeach All Saints, RG9/2330

[9] 1871 Census entry for William Mattock, Dog Drove, Holbeach St. John’s, RG10/3332

[10] Death register entry for John Mattock, 26 May 1863 Holbeach Fen, son of William Mattock, farm labourer

[11] 1881 Census entry for William Mattock, Bell End Cranes Gate, Whaplode St Mary’s, RG11/3211

[12] Lincolnshire Free Press, 19 Sep 1871 and Lynn News County Press, 23 Sep 1871

[13] Stamford Mercury, 7 Sep 1877

[14] Lincolnshire Free Press, 3 Apr 1877

[15] Lincolnshire Marriages and Banns, FindMyPast

[16] 1881 Census entry for James Mattock, Old Fen Dike “Chequers Inn”, Sutton St. James, RG11/3207

[17] Death register entry for Kezia Mattock, 8 Feb 1897 Whaplode Fen, wife of William Mattock a farm labourer

[18] Death register entry for Willam Mattock, 28 Dec 1897 Holbeach Union Workhouse, Fleet, formerly an Innkeeper of Whaplode